Category: Ship-breaking industry

Bangladesh: Ship Breaking in Chittagong – dangerous, polluting, but profitable. What is the Best way forward for this least developed nation?

Ship breaking is the most common method of ship disposal, which is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships for scrap recycling. Ship breaking allows materials from the ship, especially steel, to be recycled. Equipment on board the vessel can also be reused. There are also other ways to dispose of the ship such as, floating, use as an artificial reef, deep water sinking, or hulking.

Because of the labour cost and less environmental regulations on ship breaking, most of the ship breaking yards are located in developing countries such as Gadani in Pakistan, Aliaga in Turkey, and Chittagong in Bangladesh

Shipbreaking near Chittagong. Source: www. wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1b/ShipbreakBhatiari.jpg

The Chittagong Ship Breaking yard, in Bangladesh is the world’s second-largest ship breaking area, and possibly the most famous or infamous. The ship breaking takes place along the Sitakunda coastal strip north-west of Chittagong.

According to a report by the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Chittagong:

“Until the 1960s, shipbreaking activity was considered as a highly mechanized operation that was concentrated in industrialized countries – mainly the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and Italy. The UK accounted for 50% of the industry-Scotland ran the largest shipbreaking operation in the world. During the 1960s and 70s, ship breaking activities migrated to semi-industrialized countries, such as Spain, Turkey and Taiwan, mainly for the availability of cheaper labour and the existence of re-rolled steel market.

From early 1980s to maximize profits ship owner’s sent their vessels to the scrap yards of India, China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Vietnam, where health and safety standards are minimal and workers are desperate for work. It is estimated that over 100,000 workers are employed at ship breaking yards worldwide. Though 79 nations in the past decades have had some form of ship recycling activity, the Asian yards, which took off in the 1980s, now account for over 95% of the industry. Alang, in India, has retained its position as the world’s largest scrapping site for ocean going ships, accounting for an average of 70% of tonnage, and an average of 50% of worldwide demolition sales. Bangladesh retained second position after India in terms of volume of recycling (FIDH, 2002).”

History of the Chittagong Breaking Yards

It is said that the Ship breaking industry began in Bangladesh as a result of breaking apart a ship that was beached after a cyclone.

A severe cyclone in 1960, which killed thousands of people drove ashore a Greek ship “M D Alpine”. The MD Alpine could not be refloated and was confined to Fauzdarhat sea shore of Sitakunda Upazilla (north of Chittagong). The ship remained there for a long time.

In 1964 Chittagong Steel House bought the vessel and scrapped it. It took years to scrap the vessel, but the work gave birth to the industry in Bangladesh.

According to the Report:

“Following […] tentative beginnings, the shipbreaking sector experienced a boom in the 1980s. As developed countries like United Kingdom, Spain, Scandinavian countries, Brazil, Taiwan, and South Korea wanted to get rid of an industry, which was not in compliance with the new environmental protection standards, Bangladeshi industrialists took the opportunities allured by huge profit [to establish one].

Businessmen involved in the industry imported more and more ships and Bangladesh bit by bit began to play a major role. As a result, within a short period Bangladesh established monopoly in the international market of big ship scrapping. Statistics (DNV, 1999) show that about 52% of big ships are dismantled in Bangladesh.

Ship breakers in Bangladesh, think 1980s as the golden age. At that time, although there was already a substantial body of legislation, particularly in respect of industry, the owners of the shipbreaking yards took advantage of the laisser-faire climate (FIDH, 2002).”

The nature of this site also offered many advantages making it particularly suitable for ship breaking:

- A long, flat uniform intertidal zone,

- An extended beach with tidal difference of 6 meters,

- Protection by the Bay of Bengal,

- Stable weather conditions,

- Low labour costs,

- Some existing infrastructure (connected to the capital Dhaka by road and railway),

- Moderate enforcement of laws,

- Low level of environmental awareness,

- Huge demand of iron and steel in local market,

- Nearby location of rolling mills-essential outlet for the steel of the dismantled ships.

At present there are 24 ship breaking yards in this area , and every year 60-65 ships are either being dismantled or awaiting dismantling process (SHED, 2002).

Men rested after working at a ship-breaking yard in Chittagong, Bangladesh, Wednesday. Bangladesh is dependent on the demolition of ships for steel recovery. (Andrew Biraj/Reuters)

According to the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Chittagong Report:

“Once about 150 companies were engaged in ship scrapping activities (Rahman, 1994). At that time, more than sixty shipbreaking yards were tearing tankers and container ships apart, but paying no taxes or levies. Nor was there any oversight of the yards. The new industrial sector was also preyed upon by shady businessmen who bought ships for millions of taka using government (subject to corruption) loans and then disappeared with the loans. As time went on the banks began to be more careful and the government imposed tax on the industry.

The huge profits and scams of all types of the 1980s gave way to a less anarchical, more controlled activity. Within a decade or so the number of operating shipbreaking yards was reduced by two-thirds. Despite this change, the shipbreaking yards remain a distinct industry in Bangladesh, an activity which employs more than 100,000 blue and white collar workers for which it is impossible to obtain statistics, a dirty and dangerous industry which prefers to keep its secrets to itself and businessmen who generally consider themselves to be above the law.”

Ship Breaking in Bangladesh. Source: http://bangladeshunlocked.blogspot.co.nz/2011/05/ship-breaking-in-bangladesh.html

The Ship Breaking Yards in Bangladesh Today

Today over half the world’s redundant shipping continues to be dismantled on the same small stretch of the coast in Bangladesh. Yet now, unlike the 1980s and 1990s, work conditions are known to most of the world.

The Guardian wrote an expose on the practice of Ship breaking in May 2012 (Bangladeshi workers risk lives in shipbreaking yards):

“It will take gangs of oxyacetylene cutters nearly six months to dismember the 42,000-tonne Lara 1 [a super tanker]. In the first week, say its owners, oils, toxic sludges and other waste will be pumped out, parts of the bow and some bulkheads will be removed and the recycling will start. The cable, the steel, the generators, funnels, propellers, lifeboats, companionways, sinks, toilets, even the lightbulbs and every nut and bolt of the Lara 1 will be sold on the Bangladesh market, to be turned into construction materials, girders, metal sheets and furniture. The sheet metal will be used for riverboats and coastal craft.

“Every bit of this ship will be recycled, reused and resold. Nothing will go to waste. This ship will help build Bangladesh. We dismantle 2.5m tonnes of steel a year from Chittagong, but we need four million tonnes to keep growing,” says Hefazatur Rahman, chairman of the Mostafa group of industries, which paid $20m to buy the Lara 1 for scrap, and could make $10m profit if world steel prices rise in the next year. Or, he says, he could lose everything if they fall, as they did in 2008.”

According to Muhammed Shahin, an officer with local watchdog group Young Power in Social Action (who co wrote the report by the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Chittagong on Ship Breaking referred to above):

“In the past 10 years hundreds of men working in the 70 breaking yards have died or been maimed or poisoned. Many are from the poorest communities in the country. On average, one worker dies in the yards a week and every day a worker is injured. It seems like nobody really cares. Workers are easily replaceable to the yard owners: if one is lost they know another 10 are waiting to replace him. The government collects the taxes and turns a blind eye. Explosions of leftover gas and fumes in the tanks are the prime cause of accidents in the yards. Other accidents are caused by falls – because the men are not given safety harnesses – or workers being crushed by falling beams or plates, or electrocuted.”

In addition to the dangerous nature of the work, workers are also exposed to a number chemicals and materials that adversely affects their health. According to a report by AMRC (Asbestos in the Ship-breaking industry of Bangladesh: Action for Ban):

“In addition to steel and other useful materials, however, ships (particularly older vessels) can contain many substances that are banned or considered dangerous in developed countries. Asbestos and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are typical examples. Asbestos was used heavily in ship construction until it was finally banned in most of the developed world in the mid 1980s. Currently, the costs associated with removing asbestos, along with the potentially expensive insurance and health risks, have meant that ship-breaking in most developed countries is no longer economically viable. Removing the metal for scrap can potentially cost more than the value of the scrap metal itself. In the developing world, however, shipyards can operate without the risk of personal injury lawsuits or workers’ health claims, meaning many of these shipyards may operate with high health risks. Protective equipment is sometimes absent or inadequate. Dangerous vapours and fumes from burning materials can be inhaled, and dusty asbestos-laden areas are commonplace.”

Aside from the health of the yard workers, in recent years ship breaking has become an issue of major environmental concern. Many ship breaking yards in developing nations have lax or no environmental law, enabling large quantities of highly toxic materials to escape into the environment and causing serious health problems among ship breakers, the local population, and wildlife. Environmental campaign groups, such as Greenpeace, have made the issue a high priority for their activities.

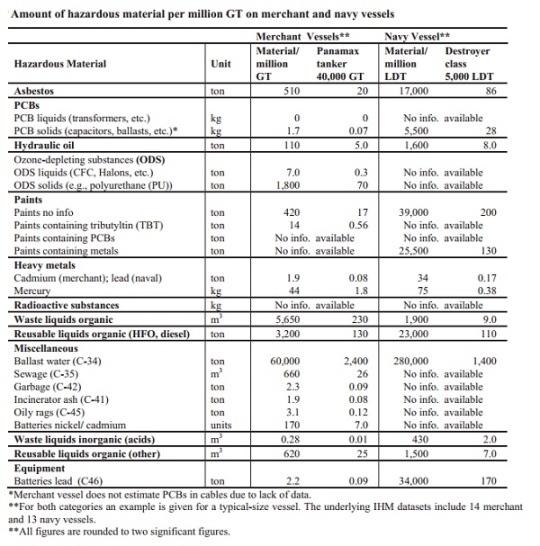

In a 2010 Report by the Word Bank (Ship Breaking and Recycling Industry in Bangladesh and Pakistan) The health and environmental contaminants of ship breaking are outlined in a table (below):

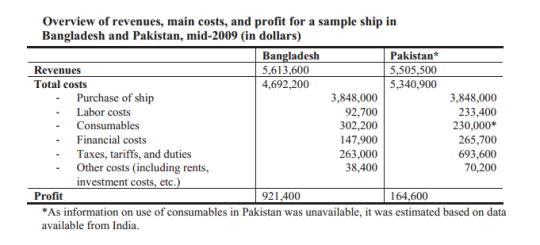

Yet this same report also outlines the value of the ship-breaking industry to Bangladesh. Notwithstanding the costs involved, Bangadeshi economic conditions make ship-breaking extremely profitable.

Costs:

- Purchase of ship

- Investment costs (for equipment and civil works such as cranes, forklifts, storage, and housing)

- Financial costs

- Labor costs

- Consumption of utilities (e.g., oxygen, LPG, diesel and electricity)

- Taxes, tariffs and duties (e.g., import taxes)

- Rents (e.g., for land use)

- Other costs (e.g., for handling hazardous waste).

The existing estimates of the price of ships vary considerably. To allow for comparison across the region, the analysis assumed that the price of a ship was [in the vicinity of] $3,848,000, excluding taxes. Investment costs for equipment and civil works have been estimated to be in the region of $441,200.

Revenues:

- Steel—the most crucial recyclable output in terms of volume and revenue. This steel is either reheated and re-rolled or melted down and re-processed.

- Other recyclable items—including non-ferrous scrap, machinery, furniture and fixtures, and ropes and cabling. Virtually, all items that can be recovered from a ship are recycled in some form.

According to ship breakers in Chittagong, approximately 85 percent of a ship is recyclable steel in the form of directly re-rollable steel (75 percent) and melting scrap (10 percent). It is estimated that ship breakers’ revenue from steel amounts to $4,771,500. Combined with the industry estimate of revenue generated by other recyclable items, total revenue is estimated at $5,613,600.

Overview of revenues, main costs, and profit for a sample ship in Bangladesh and Pakistan, mid-2009 (in dollars). Source: World Bank (2010)

What’s My Point?

My point is this – However easy it is to put point the finger, and extol developed economic virtue, the fact remains the reality depends on one’s side of the fence. The blogger Bangladesh Unlocked (Ship-Breaking in Bangladesh) provides some balance here:

“Just as in ship building, the labour force, which makes an immense contribution to employment in a country with such a high rate of real unemployment, works at higher risk levels than most jobs. The environment, too, in a country already at risk from climate change, has to be a matter of concern. But this is an industry that makes a major contribution in the country, not only to jobs, but also to the supply of iron and steel, amongst many recyclable materials, vital in an expanding economy with no natural resources in that area.

And if ships were not broken up here, where labour rates are still low, then where?

Time was such ships were simply sunk, often in insurance scams, to litter the sea bed and pollute waters as liquids and even more dangerous pollutants found their way into the water as the ships disintegrated.

There are, perhaps, few industrial vistas more spectacular than thirty, forty, fifty ships parked, side by side along the shore, being slowly disassembled by hand. And Sitakunda, in Bangladesh, is yet another world first for a country that already has the longest beach, the largest delta system and the largest Mangrove forest. And all this grew from the beaching of a small cargo ship during the tragic 1990 cyclone in which over 150,000 lost their lives, and when it was found the cyclone surge had carried the ship too far inland to be refloated, a new industry was born, thanks to the entrepreneurial initiatives of the people.”

Related articles

- Ghostly Ship Graveyards from Around the World (io9.com)

- Deadly Cargo (rasingh1970.wordpress.com)

- Controversial Shipbreaking Methods in South Asia Are Cause for Alarm (cleantechies.com)

- The Death of a Naval Vessel: a moment of poignancy (historysshadow.wordpress.com)

- Ship Photos of The Day – Ready to Ride it Out | Cyclone Mahasen Hits Bangladesh (gcaptain.com)

- Bangladesh’s other workplace catastrophes (globalpublicsquare.blogs.cnn.com)

- How do you scrap an aircraft carrier? (bbc.co.uk)

- Retired Greek ships destined to end their lives in Turkey, SE Asia (ekathimerini.com)

- Chittagong Breaking Yards (JimboJack Photo Essay)

Bangladesh: Containership Demolition – Boom Time on the Beaches?

Hellenic Shipping News post on 1 May 2013:

The last quarter of 2012 saw 58 containerships of a combined 114,118 TEU sold for demolition. This surpassed Q3 2009 – in the aftermath of the global financial crisis – to represent the greatest ever amount of capacity scrapped in a single quarter. With a further 43,744 TEU scrapped in January 2013, containership demolition continues at elevated levels, but for how long?

Scrapping in 2012

179 containerships totalling 332,922 TEU were demolished in 2012, making it the second highest year ever for scrapping after 2009, when 203 vessels of a total 379,426 TEU were demolished. Scrapping in 2009 was driven by the global financial crisis, as the 9% contraction in global container trade volumes took its toll, while ongoing charter market weakn-ess largely drove scrapping last year.

As shown on the Graph of the Month, the average size of boxships scrapped last year stood at 1,860 TEU, boosted by the scrapping of 31 3,000+ TEU containerships. This was a significant increase on the 2011 average size of 1,309 TEU, but still marginally less than 2009, when 37 x 3,000+ TEU ships were scrapped.

Younger Scrapping

Last year 52 container-ships of less than 20 years old were scrapped, while the average demolition age was just over 23. In comparison, only one vessel of less than 20 years was scrapped in 2011, while the average age of the 57 boxships demolished was 29 years, as older tonnage was cleared out. The trend for scrapping younger ships looks likely to continue in the short-term, as ten of the twenty ships scrapped in January were less than 20 years old.

Rising Panamax Scrapping

Close to 350,000 TEU is currently projected to be sold for demolition in full year 2013, 46% of which comprised of vessels of 3,000+ TEU. This represents an increasing proportion of ‘Panamax’ vessels in the pool of scrapped tonnage, a shift encouraged by a number of factors.

As the fleet ages (and owners consider scrapping younger ships) more Panamax vessels will become demolition candidates. Exacerbating this, Panamax timecharter are in the doldrums – the benchmark 6-12 month rate for a gearless 3,500 TEU vessel sits at $6,600/day, barely a third of the 1H 2011 average. In addition, the increasing uncompetitiveness of narrow-beam Panamaxes, owing to their relatively high fuel consumption compared to similar capacity wide-beam designs, is likely to encourage demolition. Even if many are still usefully employed, in the longer term, the opening of the expanded Panama Canal will further limit demand for ‘Old Panamax’ style tonnage.

Taking into account container trade growth projections, scrapping levels are currently expected to fall to 0.20m TEU in 2014. However, as the age profile of the fleet evolves, while volumes of demolition will remain cyclical, larger ships look set to in general constitute an increasing proportion of demolished tonnage.

Related articles

- Containership Scrappage Rates to Break Previous Records (worldmaritimenews.com)

- Norway’s SinOceanic orders ten 8,800 teu vessels in China (linervision.wordpress.com)

- Bankruptcies predicted as container ship crisis continues (shippingnewsandviews.wordpress.com)

- Ghostly Ship Graveyards from Around the World (io9.com)

- CSCL to Build Five 18,000 TEU Containerships (gcaptain.com)

- Greece: Diana Containerships Sells ‘Maersk Madrid’ (worldmaritimenews.com)

- Ship Finance International Places Order for Four Containerships (gcaptain.com)

- Ronsheng delivers its second containership, the HS ROME (6,588 teu) (linervision.wordpress.com)

- ESSEN EXPRESS (13,196 teu) delivered to Hapag-Lloyd (linervision.wordpress.com)